The Roman system of coinage outlived the Roman Empire itself. Prices were still being quoted in terms of silver denarii in the time of Charlemagne, king of the Franks from 768 to 8 1 4 .

The difficulty was that by the time Charlemagne was crowned Imperator Augustus in 800, there was a chronic shortage of silver in Western Europe. Demand for money was greater in the much more developed commercial centres of the Islamic Empire that dominated the southern Mediterranean and the Near East, so that precious metal tended to drain away from backward Europe.

So rare was the denarius in Charlemagne's time that twenty-four of them sufficed to buy a Carolingian cow. In some parts of Europe, peppers and squirrel skins served as substitutes for currency; in others pecunia came to mean land rather than money.

This was a problem that Europeans sought to overcome in one of two ways. They could export labour and goods, exchanging slaves and timber for silver in Baghdad or for African gold in Cordoba and Cairo. Or they could plunder precious metal by making war on the Muslim world. The Crusades, like the conquests that followed, were as much about overcoming Europe's monetary shortage as about converting heathens to Christianity. Crusading was an expensive affair and the net returns were modest. T o compound their monetary difficulties, medieval and early modern governments failed to find a solution to what economists have called the big problem of small change: the difficulty of establishing stable relationships between coins made of different kinds of metal, which meant that smaller denomi

nation coins were subject to recurrent shortages, yet also to depreciations and debasements. At Potosi, and the other places in the N e w World where they found plentiful silver (not ably Zacatecas in Mexico), the Spanish conquistadors therefore appeared to have broken a centuries-old constraint. The initial beneficiary was, of course, the Castilian monarchy that had sponsored the conquests. The convoys of ships - up to a hundred at a time - which transported 1 7 0 tons of silver a year across the

Atlantic, docked at Seville. A fifth of all that was produced was reserved to the crown, accounting for 44 per cent of total royal expenditure at the peak in the late sixteenth century.

But the way the money was spent ensured that Spain's newfound wealth provided the entire continent with a monetary stimulus. The Spanish 'piece of eight', which was based on the German thaler (hence, later, the 'dollar'), became the world's first truly global currency, financing not only the protracted wars Spain fought in Europe, but also the rapidly expanding trade of Europe with Asia.

And yet all the silver of the N e w World could not bring the rebellious Dutch Republic to heel; could not secure England for the Spanish crown; could not save Spain from an inexorable economic and imperial decline. Like King Midas, the Spanish monarchs of the sixteenth century, Charles V and Philip II, found that an abundance of precious metal could be as much a curse as a blessing. The reason? They dug up so much silver to pay for their wars of conquest that the metal itself dramatically declined in value - that is to say, in its purchasing power with respect to other goods. During the so-called 'price revolution', which affected all of Europe from the 1540s until the 1640s, the cost of food - which had shown no sustained upward trend for three hundred years - rose markedly. In England (the country for which we have the best price data) the cost of living increased by a factor of seven in the same period; not a high rate of inflation these days (on average around 2 per cent per year), but a revolutionary

increase in the price of bread by medieval standards. Within Spain, the abundance of silver also acted as a 'resource curse', like the abundant oil of Arabia, Nigeria, Persia, Russia and Venezuela in our own time, removing the incentives for more productive economic activity, while at the same time strengthening rent-seeking autocrats at the expense of representative assemblies (in Spain's case the Cortes).

What the Spaniards had failed to understand is that the value of precious metal is not absolute. Money is worth only what some one else is willing to give you for it. An increase in its supply will not make a society richer, though it may enrich the government that monopolizes the production of money. Other things being equal, monetary expansion will merely make prices higher. There was in fact no reason other than historical happenstance that money was for so long equated in the Western mind with

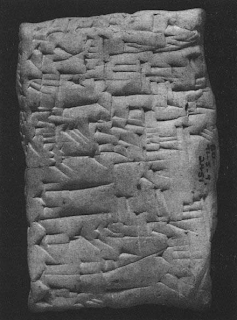

metal. In ancient Mesopotamia, beginning around five thousand years ago, people used clay tokens to record transactions in volving agricultural produce like barley or wool, or metals such as silver. Rings, blocks or sheets made of silver certainly served as ready money (as did grain), but the clay tablets were just as important, and probably more so. A great many have survived, reminders that when human beings first began to produce written records of their activities they did so not to write history, poetry

or philosophy, but to do business.

It is impossible to pick up such ancient financial instruments without a feeling of awe.

Though made of base earth, they have endured much longer than the silver dollars in the Potosi mint. One especially well-preserved token, from the town of Sippar (modern-day Tell Abu Habbah in Iraq), dates from the reign of King Ammi-ditana ( 1 6 8 3 - 1 6 4 7 BC) and states that its bearer should receive a specific amount of barley at harvest time. Another token, inscribed during the reign of his successor, King Ammi-saduqa, orders that the bearer should be given a quantity of silver at the end of a journey.

If the basic concept seems familiar to us, it is partly because a modern banknote does similar things. Just take a look at the magic words on any Bank of England note: 'I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of. . .'. Banknotes (which originated in seventh-century China) are pieces of paper which have next to no intrinsic worth. They are simply promises to pay (hence their original Western designation as 'promissory notes'), just like the clay tablets of ancient Babylon four millennia ago. 'In God We Trust' it says on the back of the ten-dollar bill, but the person you are really trusting when you accept one of these in payment is the successor to the man on the front (Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the US Treasury), who at the time of writing happens to be Lloyd Blankfein's predecessor as chief executive of Goldman Sachs, Henry M. Paulson, Jr. When an American exchanges his goods or his labour for a fistful of dollars, he is essentially trusting 'Hank' Paulson (and by implication the Chairman of the Federal Reserve System, Ben Bernanke) not to repeat Spain's error and manufacture so many of these things that they end up being worth no more than the paper they are printed on.

A clay tablet from second millennium BC

Mesopotamia, front (above) and rear (opposite). The inscription

states that Amil-mirra will pay 330 measures of barley to the

bearer of the tablet at harvest time.

Today, despite the fact that the purchasing power of the dollar has declined appreciably over the past fifty years, we remaIn more or less content with paper money - not to mention coins that are literally made from junk. Stores of value these are not. Even more amazingly, we are happy with money we cannot even see. Today's electronic money can be moved from our employer, to our bank account, to our favourite retail outlets without ever physically materializing. It is this 'virtual' money that now

dominates what economists call the money supply. Cash in the hands of ordinary Americans accounts for just I I per cent of the monetary measure known as M2. The intangible character of most money today is perhaps the best evidence of its true nature. What the conquistadors failed to understand is that money is a matter of belief, even faith: belief in the person paying us; belief in the person issuing the money he uses or the institution that honours his cheques or transfers. Money is not metal. It is trust

inscribed. And it does not seem to matter much where it is inscribed: on silver, on clay, on paper, on a liquid crystal display.

Anything can serve as money, from the cowrie shells of the Maldives to the huge stone discs used on the Pacific islands of Yap. And now, it seems, in this electronic age nothing can serve as money too.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий